|

Tom West had performed in folk singing circles in the 1950s and worked at the Smithsonian observatory in Cambridge. |

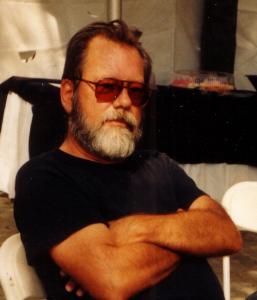

Tom West; engineer was the soul of Data General’s new machine

Thirty years ago, Tom West was thrust into a category of one, a famous computer engineer, with the publication of “The Soul of a New Machine.’’

Tracy Kidder’s book, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize and is taught in business classes and journalism schools, chronicled Mr. West’s role leading a team that built a refined version of a 32-bit minicomputer at a key juncture for the computer industry and his employer, Data General of Westborough.

The book’s success turned a quirky, brilliant, private, and largely self-taught man into a somewhat reluctant guru. Mr. West was proud of what he had accomplished, and he liked Kidder.

But Mr. West had little taste for the byproducts of fame.

“It offends me when people think they know me because of the book,’’ he told Wired magazine in 2000, more than a dozen years after he retired to relax and sail in a community where few knew he was the soul of “The Soul of a New Machine.’’

Mr. West, who performed in folksinging circles in the late 1950s and worked at the Smithsonian observatory in Cambridge before computers caught his intellectual fancy, was found Thursday in the kitchen of his Westport home, where he had collapsed. He was 71, and his family believes that he might have died of a heart attack.

“Tom was a complicated individual, and you really can’t put him in a pigeonhole,’’ said Edson de Castro, founder and former chief executive of Data General. “He was kind of a conglomerate between a hippie, an old salt, a very competent engineer, a literary buff, a harsh critic, and there’s probably more than that. You weren’t always sure which Tom you’d be talking to on any given day.’’

Kidder — who spent days, nights, and weekends with Mr. West while researching the book — called him “one of the most intense people I ever knew.’’

“He had a certain charisma, though not for everyone, to be sure,’’ Kidder said.

The book captured a moment in a lengthy career. Mr. West’s other work included research that anticipated or helped set the stage for personal computing by laptop or tablet. A driven leader, he sometimes came across as aloof when he passed people in the hallway without a word.

“My father was very intense, and you knew he was always thinking about something,’’ said his daughter Jessamyn of Randolph, Vt. “And when you went up to him, you definitely got the feeling that you were interrupting, even if he was just sitting looking out the window.’’

While he was “a remarkably loyal friend,’’ Mr. West could also be “very soft-spoken and painfully shy, which many people didn’t know,’’ said his first wife, Liz (Cohon) West of Boxborough. She called him “literally the love of my life.’’

“We couldn’t live together very well,’’ she said, “but that’s another story.’’

Creatively restless even at home, Mr. West taught himself carpentry and plumbing to renovate the family’s Boxborough residence and built an elaborate roller coaster that carried marbles from room to room in the basement of the old house.

“My dad, for me, will always be the most interesting man I’ve ever known and with one of the zaniest senses of humor,’’ said his other daughter, Katherine of Stowe, as she discussed the marble machine. “His curiosity about stuff like that was one of his greatest assets. He would delight in his Rube Goldberg contraptions and spend weeks building them.’’

Mr. West’s two marriages ended in divorce.

Cindy Woodward West of Westport, his second wife, said he had a “magical aura about him.’’

“One of Tracy’s comments says it for me,’’ she said. “Tom had a way of making ordinary things special, and I think everyone who knew Tom would say that.’’

The son of a business executive who moved often, Joseph Thomas West III attended four different high schools before following his father and grandfather to Amherst College.

Richard Todd, a former editor at The Atlantic magazine, roomed with Mr. West their senior year, and, years later, when Kidder was looking for a writing topic, Todd suggested he speak with his former roommate.

“He always had a contrarian streak and didn’t have much taste for orthodoxy, which served him very well,’’ Todd said. “He also had a very practical mind. He once said, ‘I can fix anything.’ He was sort of an autodidact and didn’t have much patience with academic life.’’

At one point, Amherst lost patience with Mr. West, too, telling him to take time off after college officials decided that he was not achieving to the level of his intelligence.

Mr. West spent most of a year working at the observatory and living in Cambridge, where he sang and played guitar in the folk music scene and encountered the likes of Joan Baez.

Returning to Amherst, he finished a bachelor’s in physics and kept working at the observatory, traveling to obscure locations around the world with a precise clock to synchronize timepieces in other observatories that marked the movement of stars and planets.

Then he worked for RCA and taught himself about computers before moving to Data General. Mr. West moved up quickly and was a senior vice president in charge of technology by the time he retired.

“His real strength was getting all the different parts of the company working together toward the endgame,’’ said Steve Wallach of Richardson, Texas, the system architect on the computer team chronicled in Kidder’s book. “For each personality, he knew what the hot button was, what to push, what not to push. He knew how to get the product out the door. Like pinball: Get the ball back and pop it again.’’

Mr. West used pinball as a metaphor to egg on his team of young computer engineers in the late 1970s when they created the Eclipse MV/8000, a 32-bit minicomputer in the days before computers began shrinking from mainframes to desktops to laptops.

“What he told them was that if you win at this level, then your reward is that you get to play again at the next level, but guess what: The next level is more difficult,’’ said Don McDougall of Palo Alto, Calif., a former vice president of technical products at Data General. “The pinball theory encapsulated how Tom motivated himself and motivated other people.’’

A service will be announced for Mr. West, who in addition to his two daughters and two former wives leaves a sister, Terry of Santa Fe.

Mr. West, who sometimes used words like jeepers in polite conversation, rather than a profane utterance that might be more to the point, was “strictly business’’ at work, said Ed McManus of Marlborough, a former director of executive support at Data General.

“He had a clear idea of what he wanted to accomplish, and you really didn’t want to get in his way,’’ McManus said. “He was one of these people who, if he had to stay overnight or over the weekend, he would do that. It wasn’t even a decision; that was something he did, and he expected others to do with him.’’

The approach was a means to an end, which, in Mr. West’s case, was building the computer that made him famous.

“Tom was almost like a rock star in the technology world,’’ said Ron Skates,

who succeeded de Castro as chief executive of Data General, which was sold to

“Everywhere he went, people knew him because of his intellect,’’ Skates said. “He could enthrall an audience with his descriptions of technology, and that sounds kind of strange. You think, ‘Why would people be enthralled with that?’ It was because of Tom.’’

Bryan Marquard can be reached at bmarquard@globe.com. ![]()